Navigation

The ability of the robot to self-localize, i.e., to autonomously

determine its position and orientation (posture) within its

surrounding environment, as well as its capacity to move from its

current posture to a desired new posture is one of the robot most

important features. Once a robot knows its posture, it is capable of

following a pre-planned virtual path or stabilizing its posture

smoothly. If the robot is part of a cooperative multi-robot team, it

can also exchange the posture information with its teammates so that

appropriate relational and organizational behaviors are

established.

In robotic soccer, these are crucial issues. If a robot knows its

posture, it can move towards a desired posture (e.g., facing the goal

with the ball in between). It can also know its teammate postures and

prepare a pass, or evaluate the game state from the team locations.

Navigation has been addressed within the SocRob project under two different

situations:

- Without the ball - This involved

- The development of a self-localization algorithm, based on

an omni-directional catadioptric vision system. The algorithm

determines the robot posture from one image frame acquired by the

catadioptric system, based on the correlation, in Hough Transform

space, of extracted information on the field geometry with an a priori

field geometric model (see picture). The posture is available for either

guiding the robot (see below) or exchange of posture information with

teammates. This algorithm is described in our RoboCup 2000 Workshop

scientific award challenge winning paper

"A

Localization Method for a Soccer Robot Using a Vision-Based

Omni-Directional Sensor", by Carlos Marques and Pedro Lima. There

is also a video (AVI) to download

illustrating this work. Notice that the robot self-localizes when it stops

(sometimes does it more than once because it detects a failure) and,

even after being "kidnapped" to a completely different posture, recovers

and can get back to its home position (on the left of the image, near the

wall).

- The implementation of guidance algorithms with obstacle

avoidance capabilities, to take the robot from its current posture (as

obtained from its odometry, periodically reset by the

self-localization algorithm) to a desired posture (e.g., robot home

position, facing the goal with the ball in between, covering own goal

between it and the ball). This is currently done when the robot does

not have ball posession, using the Freezone algorithm, described

in the paper "

Multi-Sensor Navigation for Soccer Robots". There

is also a video (AVI) to download

illustrating this work. The experiments include moving towards the ball

avoiding obstacles with periodic self-localization (reseting the odometry)

which is noticeable by the fact that, when the robot does not see the ball,

it gets back to its home position (on the left of the image, near the

wall).

An overall view of the whole navigation algorithm is provided by the IEEE

Robotics and Automation Magazine (Vol. 11, No. 3, 2004) Multi-Sensor Navigation for Non-Holonomic Robots in Cluttered Environments paper.

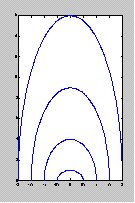

- With the ball - the work on navigation without the ball was

extended to the situation

where a robot does have the ball (i.e., a dribble is required if other

robots appear in the middle), by using a modified version of the potential

fields method, which includes a special potential field (see diagram), to take

into account the non-holonomicity of our robots, as well as constraints

on linear and angular speeds, to avoid losing the ball, given the strong

limitations on the robot "fingers" length (max one third of the ball diameter).

The work is described in the paper

A Modified Potencial Fields Method for Robot Navigation Applied to Dribbling in Robotic Soccer , and there is also

a video to download

illustrating this work.

Geometric "absolute" self-localization (i.e., posture coordinates w.r.t. a reference coordinate

system) is surely helpful, but trusting it too much in the presence of

uncertainties which sometimes cause wrong posture estimates may be

dangerous, especially if many behaviors depend on it. We are currently investigating methods of "relative" navigation (e.g., moving close to a goal, or

going around an obstacle) to combine them with our current solution.

More recent work has focused on MCL using the field lines + gyrodometry (check publications page), as well as on motion control algorithms taking advantage of the robots omnidirectional characteristic.